By Andrew C. McCarthy. Media: National Review.

The justice’s concurrence in the student-loan case clarifies the major-questions doctrine and offers a significant rebuttal of Kagan’s dissent.

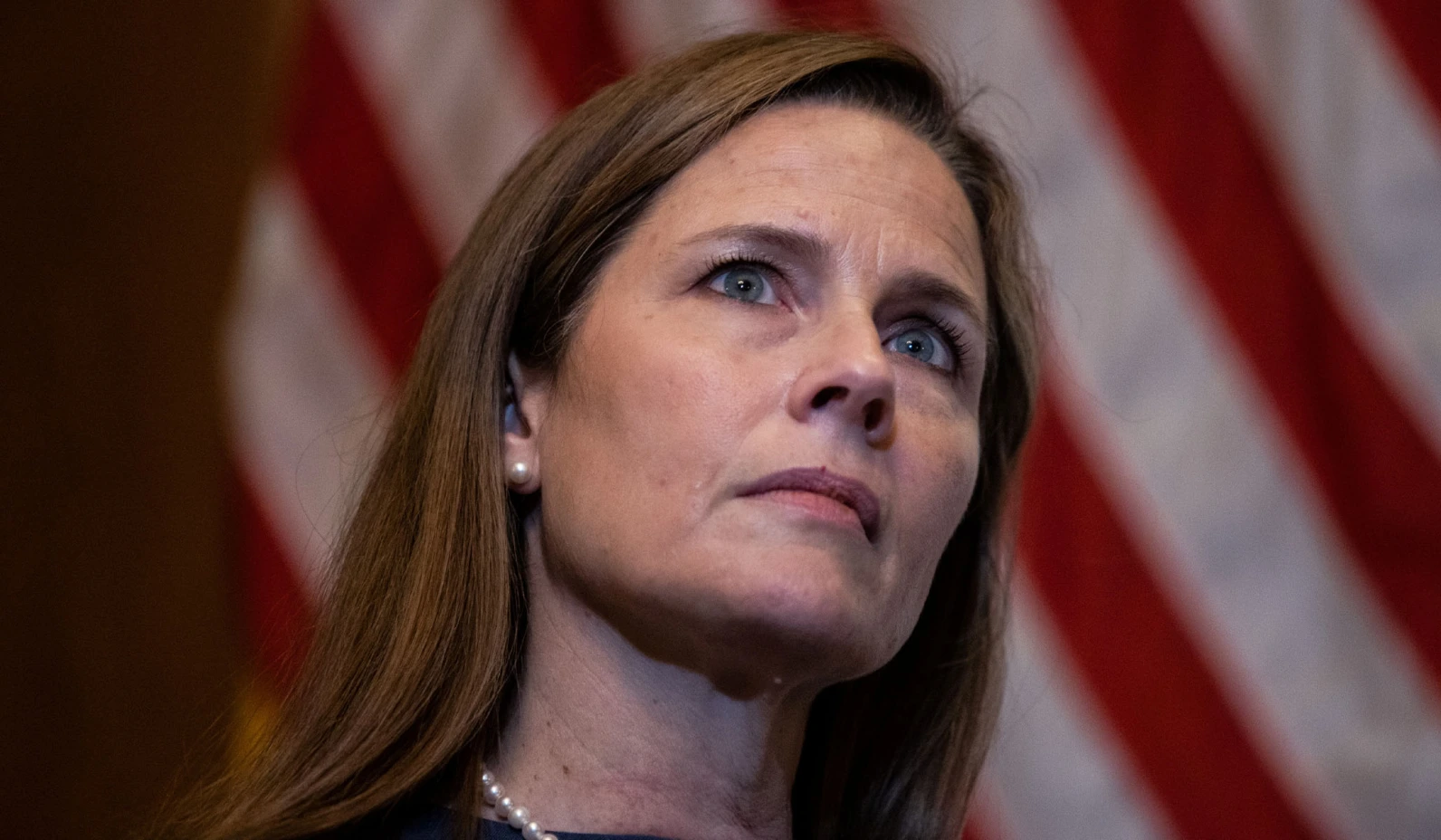

Among the most significant opinions issued in this week’s final Supreme Court rulings is Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s concurrence in the Court’s invalidation of Biden’s student-loan cancellation (Biden v. Nebraska). As a committed textualist, Justice Barrett rightly perceived the imperative of elaborating on the so-called major-questions doctrine, explaining what it does and does not permit in statutory interpretation.

The student-loan decision manifests that the Court’s conservative majority feels the tension between its avowed statutory textualism and its invocation of a doctrine that is claimed to endorse departures from text — or, at least, from the best interpretation of text. Justice Elena Kagan’s searing criticism of the major-questions doctrine as a “get-out-of-text-free card” clearly left a mark.

Justice Kagan, of course, is an administrative-state devotee who acknowledges that the Court has been forever (we hope) changed by the late, great Justice Antonin Scalia’s insistence that nothing in statutory interpretation takes precedence over the words Congress uses in its statutes — a sea change from the 20th-century era of judicial imperialism, when judges presumed a power freely to rewrite laws. Still, Kagan, the Court’s most formidable progressive, is a bureaucratic maximalist: If, read in a vacuum, the text of a statute can plausibly be construed as a delegation by Congress of enormous power to an administrative agency, then the textualist must vindicate that delegation, even if it defies history, common sense, and our Constitution’s vesting in Congress of all legislative power — i.e., the authority to enact major policy.

“But a vacuum is no home for a textualist,” Barrett counters.

Mindful of Kagan’s critique, the Court’s six-justice majority did two important things in the student-loan case.

First, Chief Justice John Roberts’s majority opinion did not rely on the major-questions doctrine to reach the result. Instead, applying an ordinary textual analysis, Roberts concluded that, in the Higher Education Relief Opportunities for Students (HEROES) Act of 2003, Congress had not delegated to the secretary of education the power to massively cancel student-loan debt.

The HEROES Act, which was enacted in the post-9/11 War on Terror era, predominantly for the benefit of military personnel, authorized the Education Department to forgive the student loans of narrow categories of borrowers (e.g., those who’d been killed, become permanently disabled, or gone bankrupt). The act empowers the DOE to “waive or modify” loans as the “Secretary deems necessary in connection with a war or other military operation or national emergency” (emphasis added).

Based on this text, President Biden deemed the Covid-19 pandemic a national emergency. He thus directed the secretary to cancel nearly half a trillion dollars in student-loan debt for millions of students. Not students who had served in the military, but virtually any students whose “hardship” is that they don’t want to repay money they borrowed for education they received (education that places them in higher potential-earnings strata even if it is not, in many instances, as valuable as they’d hoped).

Had the Court opted to decide the case based on the major-questions doctrine, it could easily have concluded that, in enacting a wartime relief provision tailored to a particular category of Americans (e.g., military personnel) who bore the hellacious costs of wartime operations, Congress was obviously not conferring on the education secretary the power to wreak economic havoc based on a medical emergency nearly two decades later — one that, though real, was nothing like a war, and whose victims were nothing like wartime casualties. Indeed, contrary to the HEROES Act, there is no real causal link in Biden’s boondoggle between the disaster cited and harms addressed. Instead, college students are a voting bloc of importance to Democrats, so progressives were scheming long before Covid to reward them with debt forgiveness and deviously used the pandemic as a pretext to do so.

But Roberts did not base the Court’s ruling on the major-questions doctrine. He based it on straightforward statutory construction. The Biden administration’s interpretation of the words “modify” and “waive” was untenable; the ordinary meaning of the words enable modest adjustments, not a wholesale transformation, of financial arrangements. Biden’s agency was not merely “waiving” loans; he was rewriting the Education Act.

The Court relied on the major-questions doctrine not to decide the case but to offer additional support for its decision. In particular, it used the doctrine to refute the Biden administration’s claim that it was Congress’s purpose, in the HEROES Act, to grant the education secretary sweeping discretion to address “unforeseen emergencies.” Relying on its decision last year in West Virginia v. EPA, and in light of the history and scope of the HEROES Act and the “economic and political significance” of a $430 billion loan cancellation, the Court concluded that it had great reason to doubt that Congress meant to confer such extraordinary authority on the Education Department.

All well and good. Nevertheless, the majority’s reasoning obviously invited Kagan to reassert her indictment of the major-questions doctrine. As expected, she zeroed in on the rule apparently derived from it that Congress must posit a “clear statement” of authority granted to an administrative agency. The majority’s claim to rely on routine statutory interpretation, she contends, is a smoke screen since, as she sees it, the words “modify,” “waiver,” and “national emergency” can plausibly be read to do exactly what the Biden administration has done. Ergo, Roberts is deciding the case based on the major-questions doctrine without saying so. She depicts the majority as textualists who recoil from text if they don’t like the policy outcome.

That brings us to the majority’s second gambit: Justice Barrett’s defense of the major-questions doctrine as applied textualism.

Barrett’s concurrence is a significant rebuttal to Kagan. Much as her mentor, Justice Scalia, rejected the label “strict constructionist,” Barrett emphasizes that a textualist is not a literalist. The major-questions doctrine, she explains, is not a license to flee from text. To the contrary, it stresses “the importance of context” (emphasis in original), providing “a tool for discerning — not departing from — the text’s most natural interpretation.”

Barrett’s contention is powerful because she takes Kagan’s critique as a serious challenge that calls for a serious answer. Canons of construction have been developed through centuries of Anglo-American jurisprudence. Consequently, they are reasonably seen as a component of the judicial power that is vested in the Supreme Court by the Constitution, as well as in the lower federal courts that Congress has established. But that’s not the end of the story. Some canons of construction can have the effect of nullifying congressional statutes — a constitutional problem.

For example, courts follow a canon of constitutional avoidance, which instructs that, if possible, judges should construe statutes in a manner that circumvents any question of constitutionality. This can crash into textualism, which admonishes that the best interpretation of a statute is the ordinary meaning of its text as understood at the time of enactment. That is, under the constitutional-avoidance canon, a judge will give a statute a less plausible meaning — though still one within the ballpark of what the text allows — if doing so is necessary to avoid a meaning that would call the statute’s constitutionality into question. That sounds sensible, but it is constitutionally fraught: By this avoidance doctrine, the Court elevates a judicial interest in dodging controversy over Congress’s undeniable Article I power to write the laws.

Barrett concedes that these canons, described as “strong-form,” can pose “a lot of trouble” for “the honest textualist” (as Scalia put it). Even though deeply rooted, they arguably exceed the judicial power. In light of that concern, Barrett rightly believes that courts should avoid the creation of new strong-form canons. Nevertheless, she concludes that the major-questions doctrine is essentially a rule of context-driven common sense — one that “is neither new nor a strong-form canon.” The doctrine doesn’t change the words that Congress has used, much less instruct courts to give the words an interpretation that is less plausible than their ordinary meaning. Indeed, it does the opposite: It derives the best interpretation of the words based on the circumstances of their enactment — based on their context.

Many things inform context, though those things can never rationalize slipping the tether of text. Statutory provisions are usually components of broader enactments that, literally and historically, can inform what the provisions mean (e.g., it should matter that the HEROES Act was obviously meant to benefit soldiers in wartime). Sometimes, a statute employs a term of art borrowed from other legal sources; such a term is understood to “bring the old soil with it.” Some laws are written into well-developed fields and are thus understood to be infused by that field’s assumptions (e.g., criminal statutes are presumed to require proof of criminal intent even if their terms are imprecise on this point). Similarly, Barrett says, the role of common sense in informing context “goes without saying.”

She gives us some examples. If a grocer tells his clerk to “go to the orchard and buy apples for the store,” that is plainly not as unqualified a directive as it sounds. If the clerk knows that the grocer keeps the shelves stocked with about 200 apples but takes the liberty of buying 1,000, then the clerk has overstepped — the purchase is so far beyond what the agent knew was customary that we must assume the principal would have said, “Get a thousand apples,” if that’s what the principal wanted.

Barrett also conjures up a hypothetical parent who hires a babysitter to watch her young children for the weekend. As she leaves, the mother hands the sitter a credit card and says, “Make sure the kids have fun.” Is it reasonable to believe that such an instruction authorized the sitter to “take the kids on a road trip to an amusement park where they spend two days on rollercoasters and one night in a hotel”? Of course not. A trip to the movies or an ice-cream parlor would make sense, sure. But “if a parent were willing to greenlight a trip that big, we would expect much more clarity than a general instruction to ‘make sure the kids have fun.’”

Think of this hypothetical instruction as a statute. It’s not that Congress didn’t use the words, “Make sure the kids have fun.” It’s that the judicial task is to construe what those words meant. That is not sensibly done in isolation, as if the task were merely to look up fun in the dictionary. Context is vital. The dictionary meaning of the text’s words is significant, of course, but that must be taken in conjunction with the all-important circumstances in which the words were uttered.

The administrative state’s turbochargers reject such limitations. If the word “waiver” can be understood in a literal, maximalist way to erase half a trillion dollars, then the secretary of education has that power, with no input from the branch of government vested with the Constitution’s power to tax, spend, and manage debt. In Justice Kagan’s construct, the only question is why the sitter only spent two days at the amusement park. After all, fun is fun, right?

But that’s not rational.

A court may not resort to the major-questions doctrine to rewrite or supplant text. The point of the doctrine is to bring rationality to text by accounting for context. That invariably includes recognizing the place of administrative agencies in our constitutional order. Barrett is not claiming that Congress may not delegate significant authority to bureaucrats. She is maintaining, however, that in our system, Congress is given the power to write laws: a power of such major consequence that the president must sign those enactments before they become law. By contrast, the agencies Congress has created are trusted only with the day-to-day administration of those laws, cabined by what the laws’ textual terms were understood to mean when enacted.

It is the task of the Court to interpret that meaning. When multiple interpretations are plausible, the best one is not necessarily found in the dictionary but in the circumstances that gave rise to the statute.

By Justice Kagan’s lights, the administrative state is a progressive overhaul of our constitutional framework, in which unelected, unaccountable bureaucrats stretch text to — and beyond — the breaking point on the theory that good governance is rule by experts.

The Court’s majority is bent on restoring constitutional order. As Justice Barrett demonstrates, the major-questions doctrine is not, pace Kagan, an artifice by which the Court departs from congressional text to impose its own policy preferences. It is a commonsense tool by which the Court gives contextually accurate meaning to the text Congress enacted.

ANDREW C. MCCARTHY is a senior fellow at National Review Institute, an NR contributing editor, and author of BALL OF COLLUSION: THE PLOT TO RIG AN ELECTION AND DESTROY A PRESIDENCY. @andrewcmccarthy

Discussion about this post