By Janice Hisle. Media: The Epoch Times.

Former President Donald Trump has galloped to an early lead in the endorsement sweepstakes—bigly, as he might say.

Some fans of Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis worry that he hurt his chances because he had not yet declared his candidacy as of May 3. Many believe DeSantis would have entered the race sooner if not for Florida’s resign-to-run law, which lawmakers have worked to adjust, presumably to accommodate a DeSantis presidential run.

In the meantime, Trump has gobbled up endorsements like a political Pac-Man, even in DeSantis’ home state.

As of May 1, Trump counted 11 Florida congressmen in his corner, including Republican Reps. Matt Gaetz, Greg Steube, and rising star Byron Donalds, one of only two black Republicans in the House of Representatives.

In contrast, DeSantis snagged only Rep. Laurel Lee (R-Brandon).

Thus far, 49 House members—about one-fourth of the Republican total—have announced they’re supporting Trump, according to BallotPedia.org.

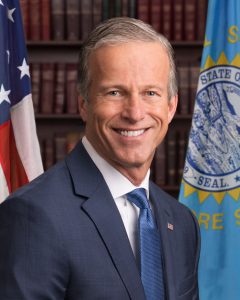

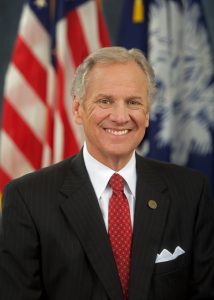

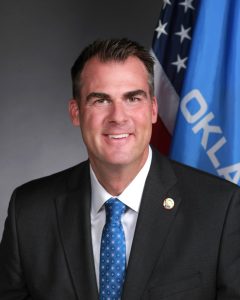

Also in the Trump column: 10 U.S. senators, plus the governors of West Virginia and South Carolina. So far, DeSantis remained scoreless in both of those categories.

If DeSantis does declare as expected, he will be playing a difficult, but not impossible, game of catch-up.

Predictive Power

These tallies matter because endorsements “have proven to be pretty predictive of who wins presidential nominating contests,” political gurus at FiveThirtyEight.com say.

Since 1972, endorsements have outperformed political polls as accurate predictors of presidential nominees, says the site, whose name derives from the total U.S. electoral college votes, 538.

According to the data, Trump currently has a total of 72 endorsements, DeSantis has 5, and former Vice President Mike Pence and former UN ambassador Nikki Haley both have 1.

Based on FiveThirtyEight’s unique scoring system, which gives more weight to prominent endorsers, Trump racked up 244 endorsement points as of May 1. The next-closest possible contender, DeSantis, trailed far behind with only 13 points.

Still, DeSantis and the other candidates have plenty of uncommitted endorsers to court. As of late April, only 11 percent of all possible endorsement points had been allotted in FiveThirtyEight’s analysis.

Because Trump is the front-runner in national polls, 2024 could be “the first incumbent-less Republican presidential primary since 2000” in which the pre-Iowa polling leader and the endorsement leader “are one and the same,” FiveThirtyEight reported.

This time around, Trump is scoring high-level endorsements much earlier than during his first presidential campaign. He had zero congressional and gubernatorial endorsements until after he had won three state primaries, FiveThirtyEight pointed out. Those endorsements came in February 2016, only nine months before the presidential election; the 2024 election is now about 18 months away.

Endorsements and polls aside, money, momentum, and messaging may matter more. And the power of being an incumbent leader also cannot be discounted—a factor on both sides during the 2024 presidential campaign.

2024 Cycle ‘Complicated’

Nonpartisan political analyst Nathan Gonzales, publisher of InsideElections.com, points out that President Joe Biden wields the power of the incumbency. But, in effect, so does Trump.

As the GOP’s two-time nominee, Trump remains the Republicans’ de facto leader.

“One of the complications to this cycle is that Biden and Trump are overshadowing the race in a way that is keeping so many people on the sidelines,” Gonzales said. “Typically, we would have a lot more candidates in on the Republican side than we do now.”

So far, six noteworthy Republicans have declared presidential runs, with few garnering elite endorsements.

Thus, the playing field is lopsided, tilted in favor of Biden on the Democrat side and in favor of Trump on the Republican side, Gonzales said.

Another factor: Gonzales said that Trump also commands “a larger-than-life” presence. His gravitas has remained unshakable, even in the face of his unprecedented criminal indictment.

And although outspoken never-Trumpers try to sabotage him, Trump is uplifted by hordes of forever-Trumpers—a fiercely loyal conservative base that GOP candidates cannot afford to alienate.

That’s why Republican politicians who are lukewarm on Trump or are secretly anti-Trump may not want to come out and endorse an opponent of his, Gonzales said. “They don’t want to anger Trump and lose an opportunity to gain his supporters,” he said.

Some Endorsers ‘Targeted’

Carol Swain, a former politics professor at Vanderbilt and Princeton universities, agrees that some endorsers are dragging their feet for that reason.

“The ones that made early endorsements of DeSantis, they may find themselves targeted and harassed for endorsing him over Donald Trump,” she told The Epoch Times.

She also believes it’s unwise to endorse early because, with many months to go in a political contest, smear campaigns and other unpredictable events may intervene and badly damage some candidates’ reputations and chances for victory.

“I’ve seen situations where people endorse too early,” she said. “They endorsed a candidate for the House or the Senate, and little was known about that person, and then later, especially toward the end of the campaign, a lot of negative information will come out.”

Once an endorsement is made, “it’s not easy to un-endorse them, to say, ‘I made a mistake;’ … they’re kind of locked in,” Swain said.

Despite that risk for endorsers, candidates love early endorsements. “From the perspective of the candidate, if you want to show momentum, you want to be able to roll out a long list of endorsers that are high-profile,” she said.

Gonzales said early endorsements could give a candidate a critical edge.

“Some of the endorsements could be a ‘bandwagon effect,’ where politicians want to be on the winning side; they want to support the winning candidate and as a candidate gained momentum,” Gonzales said. “If it looks like they’re going to win, then probably they gain endorsements.”

Because DeSantis is not the incumbent, “he can’t afford to wait too long” before announcing his candidacy, Gonzales said. “He has to draw a contrast with Trump, and he has to build his base of support. That can be done with a lot of money, and the governor appears to be able to raise a considerable amount.”

Swain points out that “money often follows the endorsements … if the people who are endorsing are committed to the point that they go out and raise money.”

On the flip side, Swain said her two unsuccessful bids for mayor of Nashville, Tennessee, taught her that money might sometimes precede endorsements.

“I was told that endorsements can be bought,” she said. “My endorsement can’t be bought, but there are some people whose endorsements come with a price tag. And you never know which endorsements came with a price tag.”

That’s part of the dirty underbelly of politics, Swain said. “I think there’s a side of politics that is corrupt enough that, if you’re inclined in that direction, you can turn, you know, any influence into profit.”

‘Disloyal’ DeSantis

Swain and Gonzales said they think Trump made a mistake by attacking DeSantis too much.

Trump has repeatedly cast DeSantis as an ingrate. Trump has said DeSantis’ initial gubernatorial campaign was dead in the water in 2018. But DeSantis reportedly begged him for an endorsement.

Trump’s endorsement helped propel DeSantis to victory—a claim Trump has repeated many times in recent months. Trump says it would be disloyal for DeSantis to become his political opponent.

That message seems to play well with Trump’s base, Gonzales said.

But the Trump endorsement wasn’t the be-all and end-all for DeSantis. During his first gubernatorial campaign, DeSantis kept appearing on Fox News, which benefited him with that Republican-heavy TV audience, Gonzales said.

And, at the risk of generating controversy, Gonzales opined that Trump’s recent messaging on this point is a little off the mark.

“Trump rose to power with a populist message, trying to be the voice for people who felt like they didn’t have a voice anymore. Trump’s current message has more to do with him and disloyalty and who is doing him wrong,” Gonzales said. “I’m skeptical that Trump will return to the White House on a message of ‘Ron DeSantis was disloyal to me.’ That just does not feel like a big-picture, winning message.”

On the other hand, DeSantis’ delay in announcing his run may be hurting him with endorsements, Gonzales said, adding, “He needs to be perceived as doing well enough in the polls for people to take the risk involved in getting behind him.”

Wait-and-See

Swain considers her endorsement “small potatoes” for any candidate. But she said many people in her circles have quickly re-endorsed Trump. “I have not endorsed anyone,” she said. “I feel that it’s very important for me to stay as the observer, as long as possible, as the independent observer.

“There are things I like about Trump. I supported him in 2016 and 2020. And there’s a lot I like about DeSantis,” Swain said.

But it gives her pause that “much of former President Trump’s campaign so far has just been focused on attacking DeSantis rather than Joe Biden.”

Trump’s message did appear to shift away from DeSantis during his last campaign speech. When the former president spoke in New Hampshire on April 27, he took shot after shot at Biden, who had just announced his reelection bid two days earlier. With rumblings that DeSantis could announce his candidacy at any time, that timing could influence how Trump handles his next speech, set for May 13 in Des Moines, Iowa, a coveted state because of its early primary caucuses.

Changing Sides

If DeSantis announces soon, as presumed, Gonzales doubts any Trump endorsers or supporters will immediately change allegiance toward the Florida governor.

“It’s possible that DeSantis is holding a number of endorsements privately that he will unveil with a public campaign announcement,” he said. “But I wouldn’t expect that initial number to equal the public endorsements Trump has garnered so far.”

At the same time, Gonzales said, “there could be people waiting for DeSantis to officially get in the race” before pledging their support.

But Gonzales also thinks “there are a large number of potential endorsers, politicians who are risk-averse and don’t plan to get involved until there’s a clear nominee.”

Many politicos are also probably waiting “to let some of Trump’s legal cases play out more” before they put their political clout on the line, Gonzales said.

In addition to facing a criminal indictment in New York, Trump is embroiled in a civil lawsuit alleging a sex offense. He also faces probes for classified documents seized from his Mar-a-Lago home in Florida, and for alleged election interference in Georgia.

Trump has cast himself as a victim of political witch hunts, a message that seems to be resonating with would-be voters. His poll numbers have been rising since his April 4 indictment.

If Trump maintains his popularity in the party, a politician who endorses DeSantis or another opponent “may take some heat from primary voters for not supporting Trump,” Gonzales said.

Impact Possible

Whether endorsements can be genuine game-changers depends heavily on the prominence of the endorser, the number of competing candidates, and other factors, Gonzales said.

“The endorsements don’t matter–until they do,” he said. “For example, Trump’s endorsement did matter in some key Senate races.”

In the 2022 Ohio Senate race, “J.D. Vance was probably going to finish third in the primary; it was crowded,” he said. “But Trump endorsed him, and that pushed Vance ahead.”

Vance had been critical of Trump but said he changed some of his opinions about the former president.

On the Democrat side, Rep. Jim Clyburn (D-S.C.) “clearly boosted Biden at a time when Biden needed boosting” in the 2020 race, Gonzales said.

“Those are high-profile examples of endorsements mattering in a sea of endorsements that have had no impact,” he said.

Discussion about this post